“Los refugiados en la carretera están en manos del destino, con sus vidas en juego.” – Robert Capa

//

“The refugees on the road are in the hands of fate, with their lives at stake.” – Robert Capa

“Los refugiados en la carretera están en manos del destino, con sus vidas en juego.” – Robert Capa

//

“The refugees on the road are in the hands of fate, with their lives at stake.” – Robert Capa

“No hace falta recurrir a trucos para hacer fotos… No tienes que hacer posar a nadie ante la cámara. Las fotos están ahí, esperando que las hagas. La verdad es la mejor fotografía, la mejor propaganda.”

– Robert Capa.

//

“No need to resort to tricks to take photos… You do not have anyone to pose for the camera. The pictures are there, waiting for you to. The truth is the best shot, the best propaganda.”

– Robert Capa.

Desde la década de 1940, Robert Capa fotografió regularmente en color para las revistas de la época (Holiday, Illustrated, Life, etc.), pero la mayor parte del trabajo nunca ha sido impreso, visto, o incluso estudiado antes. De hecho, este aspecto de su carrera prácticamente se había olvidado. La curadora Cynthia Young seleccionó 125 imágenes en color entre los 4.200 diapositivas conservados en el Archivo Capa en el ICP, la mayoría de los cuales habían llegado a ser casi inutilizables debido al deterioro del color. Gracias a las tecnologías digitales, se escanearon las diapositivas, se corrigió el color, y se imprimieron, y el público ahora será capaz de descubrir estas extraordinarias fotografías de todo un aspecto completamente nuevo de la obra de Capa, mucho más feliz y ligero que la famosa fotografía de guerra en blanco y negro por la que se le conoce.

//

From the 1940s, Robert Capa photographed regularly in color for the magazines of the day (Holiday, Illustrated, Life, etc.), but the majority of the work has never been printed, seen, or even studied before. In fact, this aspect of his career had virtually been forgotten. Curator Cynthia Young selected 125 color images among the 4,200 slides preserved in the Capa Archive at ICP, most of which had become almost unusable because of color deterioration. Thanks to digital technologies, the slides were scanned, color corrected, and printed, and the public will now be able to discover these extraordinary photographs–a whole new aspect of Capa’s work, much happier and lighter than the famous black-and-white war photography for which he is known.

(via: http://fansinaflashbulb.wordpress.com/2014/01/30/capa-in-color/)

El soldado Houston S. Riley, durante el desembarco. // Soldier Houston S.Riley while landing.

Hoy se cumplen 70 años del desembarco de Normandía.

Houston S. Riley, de la compañía Fox, se arrastraba hacia la playa bajo la metralla, esquivando cuerpos y material abandonado de los que iban por delante. Los obstáculos que los alemanes habían plantado en medio de la arena para impedir la llegada de los tanques servían de parapeto momentáneo, y hasta uno de esos erizos metálicos llegó desde la lancha. Allí se encontró con un tipo que llevaba escrita la leyenda ‘Press’ en sus galones. “¿Pero qué hace ese tipo con una cámara aquí?”. Era Robert Capa.

Durante años el rostro anónimo de una de las fotos más famosas de la II Guerra Mundial se atribuyó al sargento Regan, de Atlanta. Había sido uno de los jóvenes estadounidenses que había desembarcado y sobrevivido al infierno de Omaha Beach, una de las playas designadas por los aliados para la liberación de Europa. Pero el historiador Lowell L. Getz descubrió que, en realidad, se trataba de otro de la compañía Fox: el espigado Houston S. Riley, un chaval de Mercer Island, en el estado de Washington.

Riley, que siempre se ha reconocido en la foto de Capa, no era un inexperto. Había desembarcado en Marruecos con las tropas del general Patton, así como en Sicilia y en Italia ese mismo año. Su compañía fue elegida para viajar en la primera oleada de invasión por ese mismo motivo.

En ese momento de confusión, ruido atroz y muerte a su alrededor, el soldado Riley fue herido de dos balazos. El primero le rozó el cuello y el segundo se quedó incrustado en su espalda. Otro militar tiró de él hacia la arena desde un lado. Cómo él mismo recuerda a una entrevista concedida a Getz, “el fotógrafo me agarró desde el otro lado y ambos me sacaron del agua”. Es decir, que Capa pudo haberle salvado la vida, a pesar de que temía por la suya propia, como dejó escrito en su autobiografía, ‘Ligeramente desenfocado’: “La cámara me temblaba en las manos. Era un tipo de miedo nuevo que me estremecía desde el último pelo hasta la punta del pie”. La operación se inició a las 6:30 de la mañana después de un intenso bombardeo.

En el camino hacia la playa muchos soldados vomitaron en la lancha. La embarcación, con matrícula LCI85, chocó contra una banco de arena y los militares tuvieron que avanzar más de 100 metros hasta la orilla. Muchos se ahogaron por el peso del equipo y la mayoría tardó media hora o más en cruzar esos 100 metros de la muerte. El 40% de esos soldados de la primera oleada de Omaha ‘la sangrienta’ resultaron muertos o heridos de gravedad. Además, y a diferencia del resto de playas, la de Omaha estaba custodiada por una división alemana de veteranos del frente ruso, mucho más duros y expertos que los adolescentes que esperaban en el resto de objetivos de aquella mañana, destinados a británicos, franceses y canadienses.

Capa habla en su libro de un soldado con el que compartió un obstáculo, pero nunca supo su nombre. Riley tampoco volvió a ver a Capa, que murió en 1954 en Vietnam, pero sí llegó a conocer al soldado Regan, de Atlanta, con el que muchos le habían confundido años antes. “El reconoció que no se parece al de la foto, así que nos reímos mucho con eso”, le dijo en la entrevista a Lowell L. Getz. Hoy sigue viviendo en la casa que sus padres construyeron junto a la playa.

//

Today is the 70th anniversary of the Normandy landings.

Houston S. Riley, of Fox Company, crawled onto the beach under fire, dodging bodies and abandoned material from those who were ahead. The obstacles that the Germans had planted in the middle of the sand to prevent the arrival of tanks served as momentary parapet, and even one of those metal hedgehogs came from the boat. There he met a guy who had written the legend ‘Press’ in their stripes. “What was that guy with a camera here?”. It was Robert Capa.

For years the anonymous face of one of the most famous photographs of World War II was attributed to Sergeant Regan, from Atlanta. He had been one of the young Americans that had landed and survived the hell of Omaha Beach, one of the beaches designated by the Allies for the liberation of Europe. But the historian Lowell L. Getz discovered that in fact he was another one from Fox Company: eared Houston S. Riley, a boy of Mercer Island in Washington state.

Riley, who has always been recognized by himself in Capa’s photo was not a novice. He had landed in Morocco with the troops of General Patton, as well as in Sicily and Italy that year. His company was chosen to fly in the first wave of invasion for the same reason.

In that moment of confusion, noise and excruciating death about him, soldier Riley was wounded by two bullets. The first grazed his neck and the second became embedded in his back. Another soldier pulled him to the sand from one side. How he remembers an interview with Getz, “the photographer grabbed me from the other side and they took me out of the water.” I.e. that Capa could have saved his life, although he feared for his own, as he left written in his autobiography, ‘Slightly out of focus’: “The camera shaking in my hands. It was a new kind of fear that I shuddered from the last hair to toe”. The operation began at 6:30 in the morning after a heavy bombardment.

On the way to the beach vomited many soldiers in the boat. The vessel, registered LCI85, struck a sandbar and the military had to move more than 100 meters to shore. Many were drowned by the weight of the equipment and most took half an hour or more to cross the 100 meters death. 40% of those soldiers of the first wave of Omaha ‘bloody’ were killed or seriously injured. Moreover, unlike the other beaches, Omaha was guarded by a German division veterans of Russian front, much harder and skilled than the teenagers waiting in the other objectives that morning, for British, French and Canadian.

Capa speaks in his book about a soldier with whom he shared an obstacle, but never knew his name. Riley also never saw again Capa, who died in 1954 in Vietnam, but came to know the soldier Regan, of Atlanta, with which many mistook him years before. “He recognized that does not look like to the one in the picture, so we laughed a lot with that,” he said in the interview with Lowell L. Getz. Today still lives in the house that her parents built along the beach.

(via: http://www.elmundo.es/internacional/2014/06/06/5391423ce2704e49188b456c.html)

Hoy se conmemora el centenario del nacimiento de Endre Friedmann (conocido mundialmente como Robert Capa).

Catorce grandes fotógrafos eligen para ABC su instantánea preferida de uno de los mayores genios del siglo XX.

Gervasio Sánchez elige la foto de la niña que en enero de 1939 espera ser evacuada en Barcelona. Está sentada y apoyada sobre unos sacos y destacan sus intensos ojos.

“Siempre he preferido a Endre Friedmann, que fue su verdadero nombre, que al ficticio: Robert Capa. Siempre he preferido al fotógrafo compasivo que al mito. Para mí, es inmortal no por los riesgos que asumió para realizar sus fotografías sino por su sensibilidad a la hora de dignificar a las víctimas de los conflictos armados. Sus fotos que más me gustan son las que hizo en la retaguardia, donde documentó la desolación de los refugiados y los sobrevivientes. Siempre creyó que una imagen tiene que documentar y emocionar. Sabía (algo que siempre digo a los jóvenes fotógrafos) que si no estás dispuesto a sufrir el impacto del dolor en tu interior nunca podrás transmitir con decencia.” – Gervasio Sánchez

//

Today marks the centenary of the birth of Endre Friedmann (known worldwide as Robert Capa).

Fourteen great photographers choose for ABC newspaper their preferred instant from one of the greatest geniuses of the twentieth century .

Gervasio Sánchez choose the photo of the girl that in January 1939 in Barcelona is waiting to be evacuated. She is sitting and resting over some sacks and highlight her intense eyes .

“I’ve always preferred to Endre Friedmann, it was his real name, than the fictional Robert Capa. I’ve always preferred the photographer compassionate than the myth. For me, he is immortal not by the risks he took to make his photographs but his sensitivity when dignify the victims of armed conflicts . His photos that I more like are the ones made in the rear, where documented the desolation of refugees and survivors. He always believed that a picture must document and excite. He knew (something I always tell to young photographers) that if you’re not willing to suffer the impact of pain inside you, you won’t be able to convey decency ever.” – Gervasio Sánchez

(via: http://www.abc.es/cultura/arte/20131019/abci-robertcapacentenario-201310182201.html)

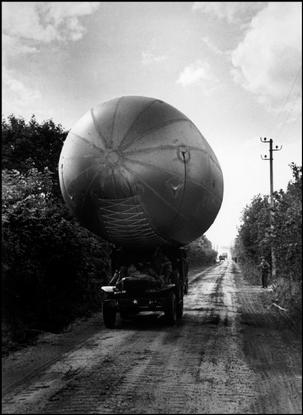

Este año se celebra la edición número 100 del Tour de Francia, sin duda la más famosa carrera de bicicletas en el mundo. Muchas cosas han cambiado. Aquí están las imágenes captadas por Robert Capa durante el Tour de 1939, que fue ganado por el ciclista belga Sylvère Maes, quien también ganó el Tour de 1935.

//

This year marks the 100th edition of the Tour de France, arguably the most famous bike race in the world. Much has changed. Here are images captured by Robert Capa during the 1939 Tour, which was won by the Belgian cyclist Sylvère Maes, who also won the 1935 Tour.

(via: http://fansinaflashbulb.wordpress.com/2013/07/21/1939-tour-de-france/)

Ayer fue el aniversario del Día-D. Las fotografías de Robert Capa de la batalla son milagrosas por muchas razones, pero su mayor poder reside en su naturaleza fundamental, la forma en que han influido en nuestra “memoria” colectiva de uno de los momentos más significativos de la historia moderna.

FRANCIA. Normandía. 06 de junio 1944. Desembarco de las tropas estadounidenses en Omaha Beach. Foto © Robert Capa / Magnum Photos / ICP

//

Yesterday was the anniversary of D-Day. Robert Capa’s frames from the battle are miraculous for many reasons, but their greatest power lies in their seminal nature, the way they have influenced our collective “memory” of one of modern history’s most significant moments–>http://bit.ly/14jgXId

FRANCE. Normandy. June 6th, 1944. Landing of the American troops on Omaha Beach. Photo © Robert Capa/Magnum Photos/ICP

(via: http://www.magnumphotos.com/)

El 17 de abril de 1945 la Segunda Guerra Mundial se acercaba a su final. Capa se había unido a la Segunda División del 1er Ejército a su paso por la periferia de Leipzig, donde entró sin apenas oposición. Acompañó a un pelotón de ametralladoras a un edificio de apartamentos en la esquina de la calle principal. En el quinto piso, dos soldados disparaban con el arma puesta sobre una mesa junto a una ventana. En un momento dado, salieron al balcón del apartamento, desde el que tenían una vista directa a lo largo de la carretera principal sobre el puente, para proporcionar una buena cobertura a las tropas que avanzaban. Capa pensó que desde allí podría tomar una buena fotografía de los soldados que pudieran estar en el puente y que podría ser, tal como refiere en su autobiografía “Ligeramente desenfocado”, “la última fotografía de la guerra para mi cámara”.

Utilizando alternativamente sus dos cámaras, fotografió a los soldados disparando a través de la ventana y, después, fuera, desde el balcón. De repente, frente a él uno de los soldados recibió un disparo de un francotirador alemán y cayó muerto. Capa disparó algunas fotografías en las que la sangre del soldado fluye en un charco que se extiende por el suelo. Son las fotos más crudas de toda la carrera de Capa.

Life no publicó las fotografías hasta el número del 14 de mayo, que anunció el fin de la guerra en Europa, sugiriendo, como afirmaría el propio Capa, que tenía “la fotografía del último soldado en caer”, aunque lo cierto es que la guerra continuó con numerosas muertes durante tres semanas más.

Life tapó las caras de los dos soldados en el balcón a fin de que la familia del fallecido no supiera de la muerte de su hijo antes de recibir la notificación oficial por parte del Ejército estadounidense.

Sobre las fotografías, la revista reprodujo cuatro versos del poema de A. E. Housman:

“Por tanto, aunque lo mejor es malo,

muchacho, ponte en pie y haz todo lo que puedas;

ponte en pie y lucha y ve a quien te ha de matar,

y recibe la bala en el cerebro”

//

On April 17, 1945 World War II was nearing its end. Capa had joined the Second Division of the 1st Army on its way through the outskirts of Leipzig, where it entered with little opposition. Accompanied a platoon of machine guns at an apartment building on the corner of Main Street. On the fifth floor, two soldiers were shooting with the gun placed on a table next to a window. At one point, they went to the balcony of the apartment, since they had a direct view over the main road over the bridge, to provide good cover for the advancing troops. Capa thought from there he could take a good photograph of soldiers who could be on the bridge and could be, as relates in his autobiography “Slightly out of focus”, “the last picture of the war for my camera”.

Using his two cameras alternately, photographed soldiers shooting through the window and then out from the balcony. Suddenly, in front of him one of the soldiers was shot by a German sniper and died. Capa shot some photographs that soldier’s blood flowing in a pool that stretches across the floor. They are the most hard photos made by Capa in his whole work.

Life magazine did not publish the photographs until the number of May 14, when they announced the end of the war in Europe, suggesting, as Capa assert himself, he had “the picture of the last soldier to fall”, but the fact is that the war continued with numerous deaths for three weeks.

Life covered the faces of the two soldiers on the balcony so that the deceased’s family did not know of his son’s death before receiving official notification from the U.S. Army.

Over the pictures, the magazine reprinted four verses of the poem of A. E. Housman:

“Therefore, though the best is bad,

boy, stand up and do your best;

stand up and fight and see who has to kill you,

and receive the bullet in the brain”

A pesar de que una vez terminada la Segunda Guerra Mundial había prometido no fotografiar una guerra nunca más, Capa moriría casi exactamente diez años más tarde del desembarco de Normandía al pisar una mina el 25 de mayo de 1954 mientras acompañaba a un regimiento del ejército francés en un peligroso avance durante la Guerra de Indochina a petición de la revista Life.

A pesar de que una vez terminada la Segunda Guerra Mundial había prometido no fotografiar una guerra nunca más, Capa moriría casi exactamente diez años más tarde del desembarco de Normandía al pisar una mina el 25 de mayo de 1954 mientras acompañaba a un regimiento del ejército francés en un peligroso avance durante la Guerra de Indochina a petición de la revista Life.

Aquella noche, siguiendo su norma de aproximarse al máximo a la acción, abandonó el jeep en el que viajaba para adelantarse y fotografiar a las tropas según avanzaban, y al cabo de unos minutos terminó por pisar una mina que voló su pierna izquierda y le causó una profunda herida en el pecho. Aunque sobrevivió a la explosión en sí, para cuando consiguieron llevarlo a un hospital de campaña ya había muerto, eso sí, sin soltar en ningún momento su cámara.

Robert Capa solía decir “si tus fotos no son suficientemente buenas es porque no estás lo suficientemente cerca”

//

Although once the Second World War finished he had promised not to shoot a war anymore, Capa die almost exactly ten years after the Normandy invasion, when he stepped on a mine on May 25, 1954 while escorting a French army regiment on a dangerous development during the Indochina War, at the request of Life magazine.

That night, following his rule about being as close as possible to the action, abandoned the jeep he was riding to go ahead and shoot the troops as they advanced, and after a few minutes ended up stepping on a mine which blew his left leg and caused him a deep wound in the chest. Although he survived the explosion itself, so when they got him to a hospital had died, yes, holding his camera at any time.

Robert Capa used to say “if your photographs are not good enough is because you’re not close enough”

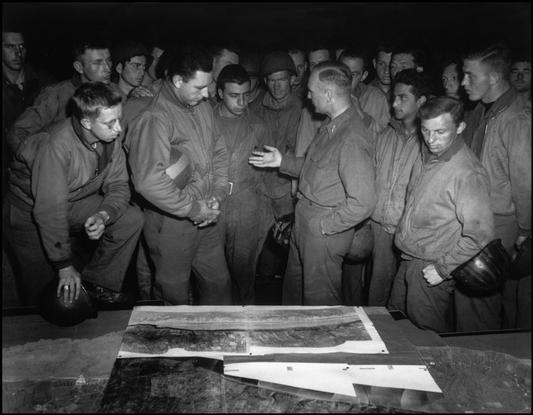

En la mañana del 6 de junio de 1944 entre los miles de soldados que se disponían a desembarcar en las playas de Normandía con el objetivo de liberar Europa del yugo del régimen nazi, y entre otros cuantos periodistas y fotógrafos, se encontraba el conocido fotógrafo Robert Capa.

En la mañana del 6 de junio de 1944 entre los miles de soldados que se disponían a desembarcar en las playas de Normandía con el objetivo de liberar Europa del yugo del régimen nazi, y entre otros cuantos periodistas y fotógrafos, se encontraba el conocido fotógrafo Robert Capa.

En concreto, Capa se encontraba a bordo del USS Samuel Chase, barco en el que viajaba la Compañía E (Easy) del 16º Regimiento de la 1ª División de Infantería, compañía con la que Capa, haciendo honor a su propio dicho de que «si tus fotos no son lo suficientemente buenas es que no estás lo suficientemente cerca», decidió desembarcar durante la primera oleada de asalto en la playa Omaha en lugar de esperar a la relativa seguridad de sucesivas oleadas.

La Playa Omaha terminaría por ser conocida como Omaha la Sangrienta, pues fue la playa en la que las tropas aliadas encontraron mayor resistencia por parte de los alemanes, hasta el punto de que los mandos de la invasión llegaron a considerar la posibilidad de desviar las tropas destinadas a Omaha a la Playa Utah, donde apenas se había encontrado resistencia. Al final no fue necesario porque la infantería y los Rangers, aún a pesar de que prácticamente todos sus oficiales y sargentos estaban muertos o heridos, consiguieron abrirse paso entre los campos de minas y el alambre de espino usando torpedos bangalore, tal y como se puede ver -con más o menos precisión histórica- en los primeros minutos de la película “Salvar al soldado Ryan”.

En el caos de los primeros momentos de la invasión, la compañía Easy terminó por tomar tierra por error en la zona llamada Easy Red de la playa Omaha, cerca de Collevile-Sur-Mer, y una vez fuera de la lancha de desembarco Capa se puso a trabajar con sus dos Contax II equipadas con objetivos de 50 mm, exponiendo cuatro carretes antes de embarcar de vuelta a Inglaterra.

De esos cuatro carretes probablemente la foto más famosa sea la que precede a este párrafo, aunque la calidad de la imagen es mala. En el laboratorio de la revista Life en Londres, para quien trabajaba Capa en aquel entonces, el ayudante de laboratorio Dennis Banks, a quien presionaban para que tuviera las fotos listas de una vez, pues las fotos de Capa llegaban con más de un día de retraso y eran las únicas en las que se veían imágenes del desembarco propiamente dicho, las secó a una temperatura demasiado elevada para acelerar el proceso, lo que hizo que la emulsión se derritiera… y sólo se pudieron salvar once fotogramas, conocidos como “The Magnificent Eleven”, de los que Life publicó diez, explicando que las imágenes se veían «ligeramente desenfocadas» porque en el nerviosismo del momento las manos del fotógrafo temblaban, algo que Capa siempre negó.

De esos cuatro carretes probablemente la foto más famosa sea la que precede a este párrafo, aunque la calidad de la imagen es mala. En el laboratorio de la revista Life en Londres, para quien trabajaba Capa en aquel entonces, el ayudante de laboratorio Dennis Banks, a quien presionaban para que tuviera las fotos listas de una vez, pues las fotos de Capa llegaban con más de un día de retraso y eran las únicas en las que se veían imágenes del desembarco propiamente dicho, las secó a una temperatura demasiado elevada para acelerar el proceso, lo que hizo que la emulsión se derritiera… y sólo se pudieron salvar once fotogramas, conocidos como “The Magnificent Eleven”, de los que Life publicó diez, explicando que las imágenes se veían «ligeramente desenfocadas» porque en el nerviosismo del momento las manos del fotógrafo temblaban, algo que Capa siempre negó.

//

On the morning of June 6, 1944 among the thousands of soldiers who were preparing to land on the beaches of Normandy with the aim of liberating Europe from the yoke of the Nazi regime, and among a few other journalists and photographers, was the renowned photographer Robert Capa.

In particular, Capa was aboard the USS Samuel Chase, boat where there was riding the Company E (Easy) from 16 Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, a company with which Capa, true to his own saying that “if your pictures are not good enough, you’re not close enough, “he decided to land during the first wave of assault on Omaha Beach instead of waiting for the relative safety of successive waves.

Omaha Beach would eventually become known as Bloody Omaha, as was the beach where Allied troops found more resistance from the Germans, to the point that the commanders of the invasion came to consider the possibility of diverting troops Omaha aimed at Utah Beach, where it had met only resistance. In the end it was not necessary because the infantry and Rangers, even though virtually all of its officers and sergeants were killed or wounded, managed to break through minefields and barbed wire using bangalore torpedoes, as can be see-more or less historically accurate- in the first minutes of the movie “Saving Private Ryan.”

In the chaos of the early stages of the invasion, Easy Company eventually fails to land in the area called the Easy Red Omaha Beach, near Collevile-Sur-Mer, and once out of the landing craft Capa got to work with his two Contax II equipped with 50 mm lenses, setting four rolls of film before shipping back to England.

From these four rolls of film probably the most famous picture is the one that precedes this paragraph, though image quality is poor. In the laboratory of Life magazine in London, for which Capa worked back then, the lab assistant Dennis Banks, who lobbied to have the photos ready at once, as the photos of Capa arrived with more than a day late and were the only ones who saw images of the landing itself, he dried them at a too high temperature to accelerate the process, making the emulsion to melt … and only eleven frames were saved, known as “The Magnificent Eleven “, of which Life published ten, explaining that the images looked” slightly out of focus “because the nervousness of the moment the photographer’s hands trembled, something always denied by Capa.