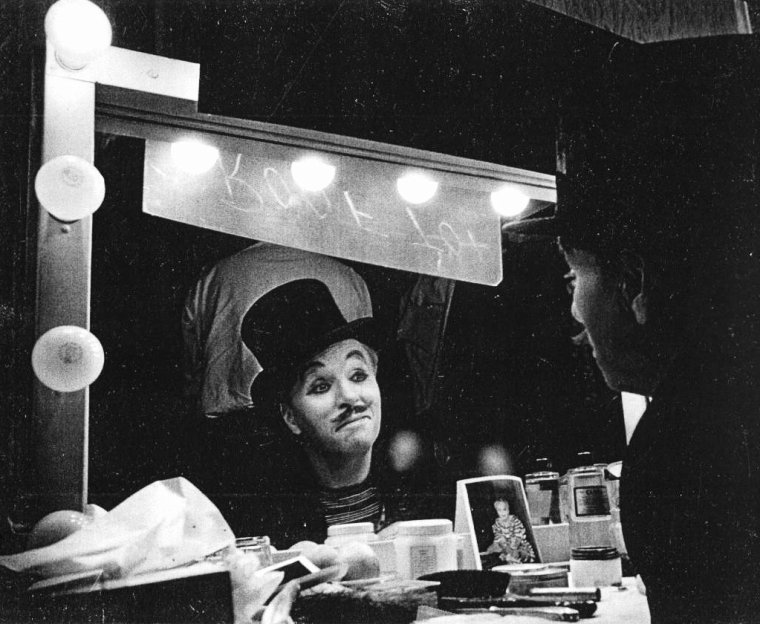

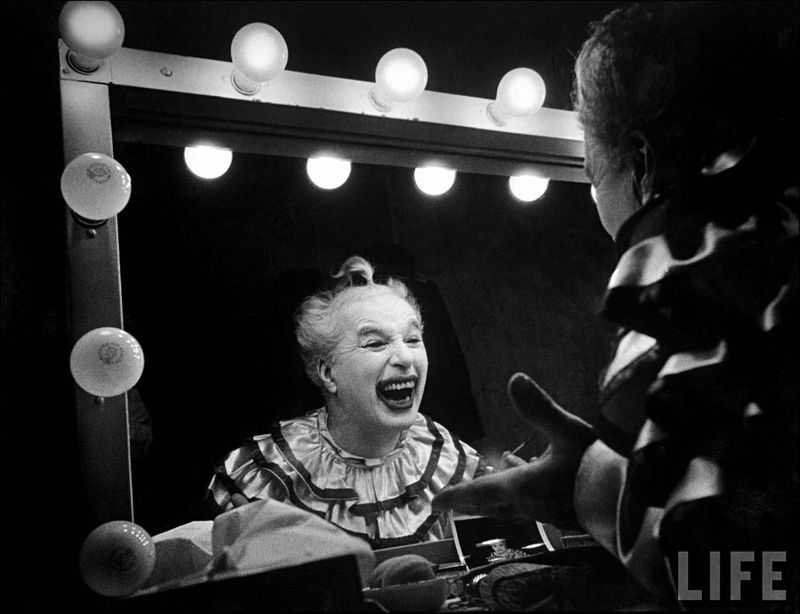

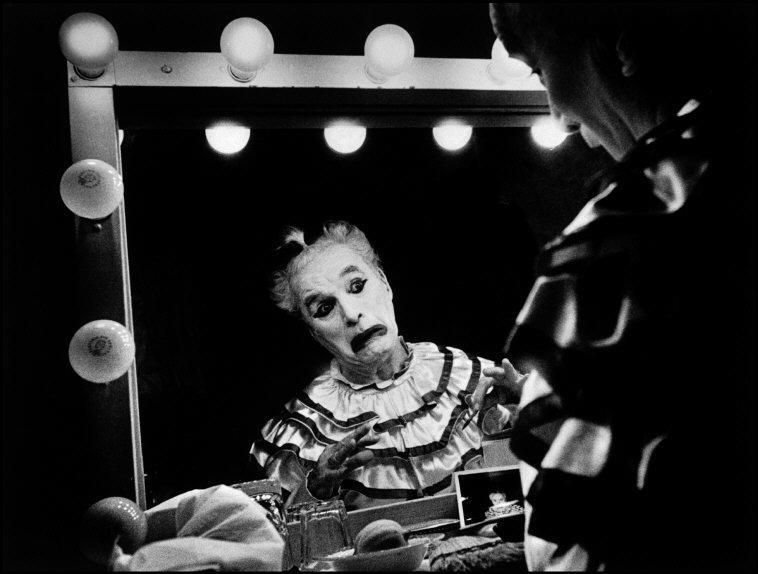

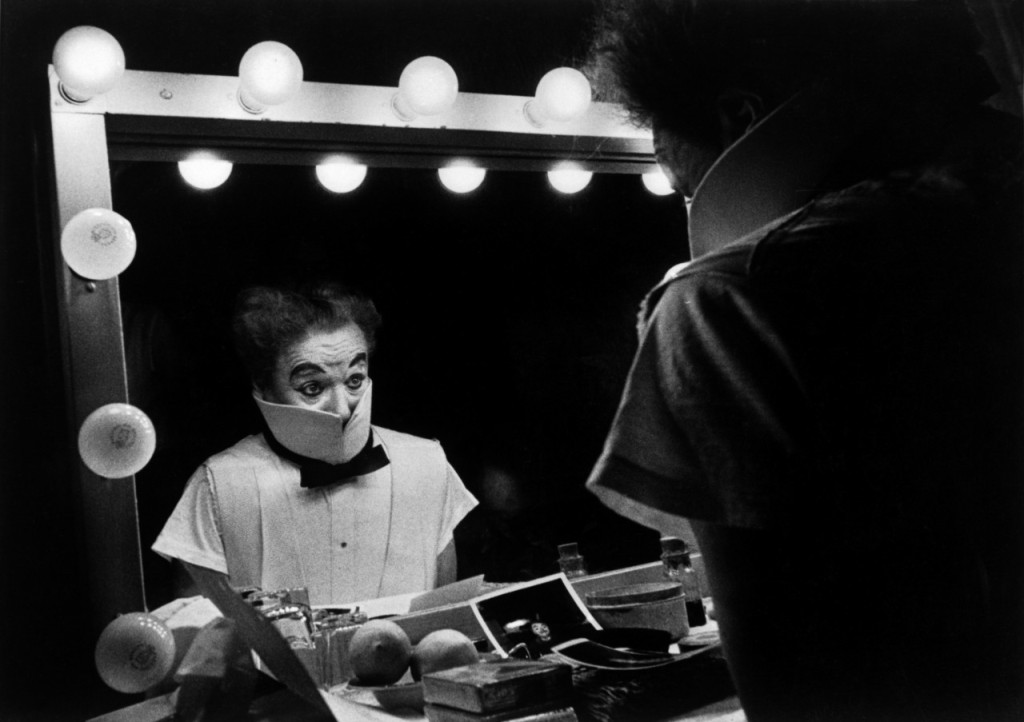

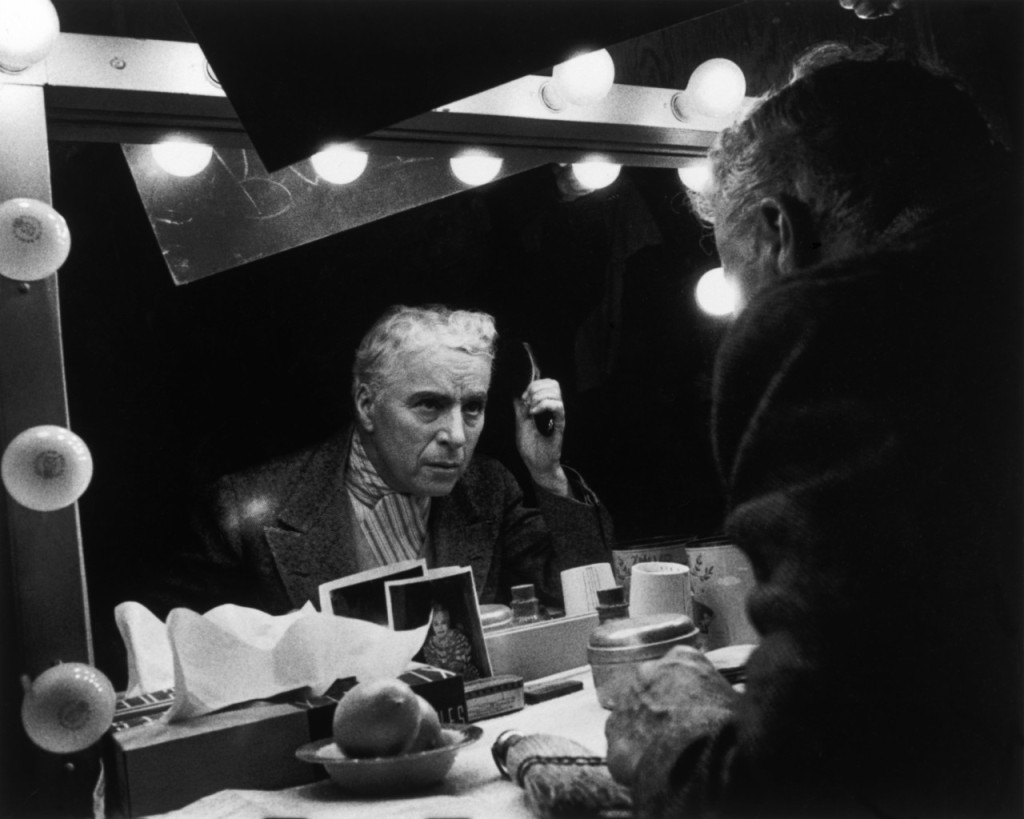

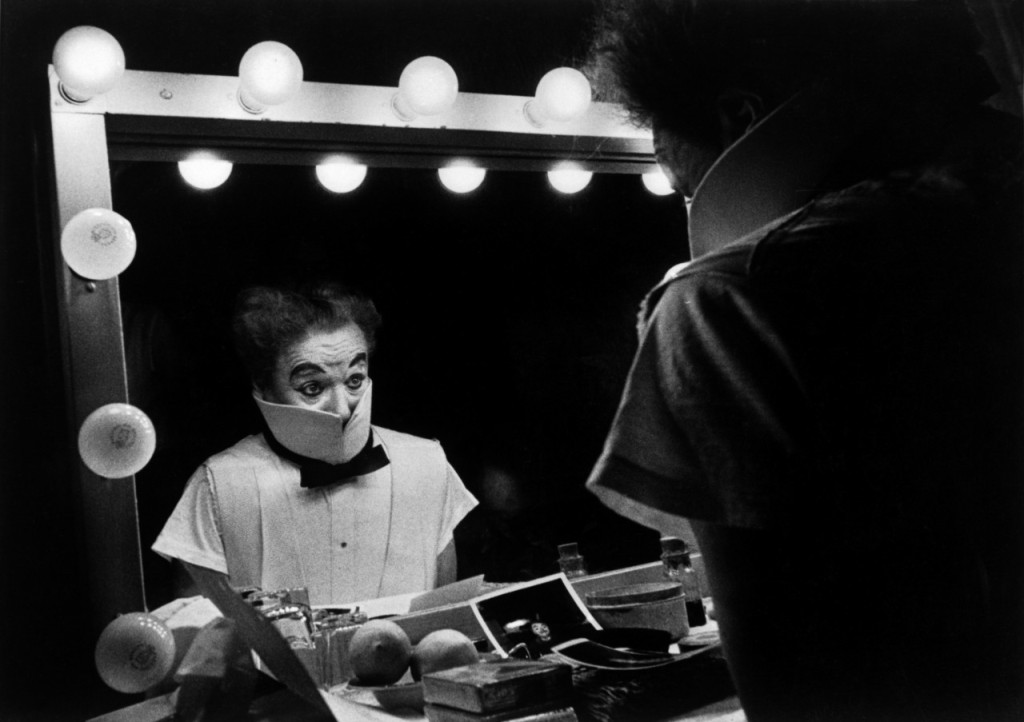

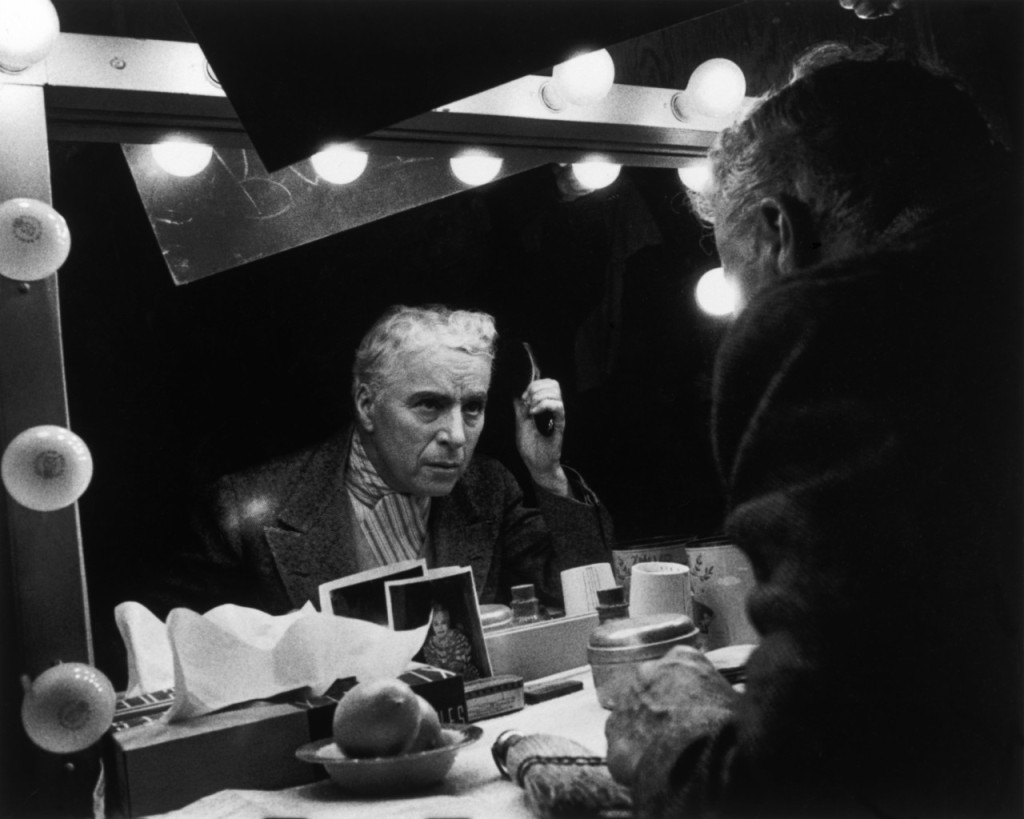

Charlie Chaplin durante el rodaje de su película “Candilejas”. Hollywood, California, 1952.

//

Charlie Chapin during the shooting of his movie “Limelight”. Hollywood, California, 1952,

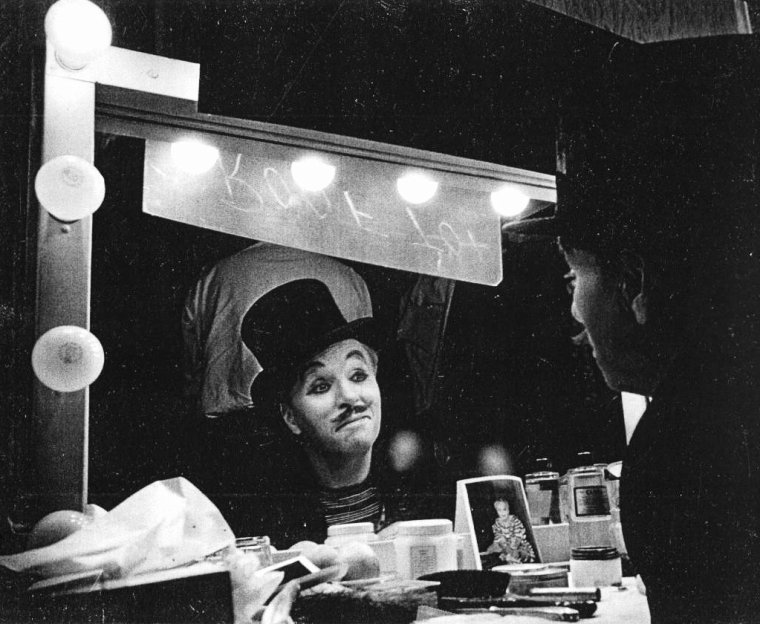

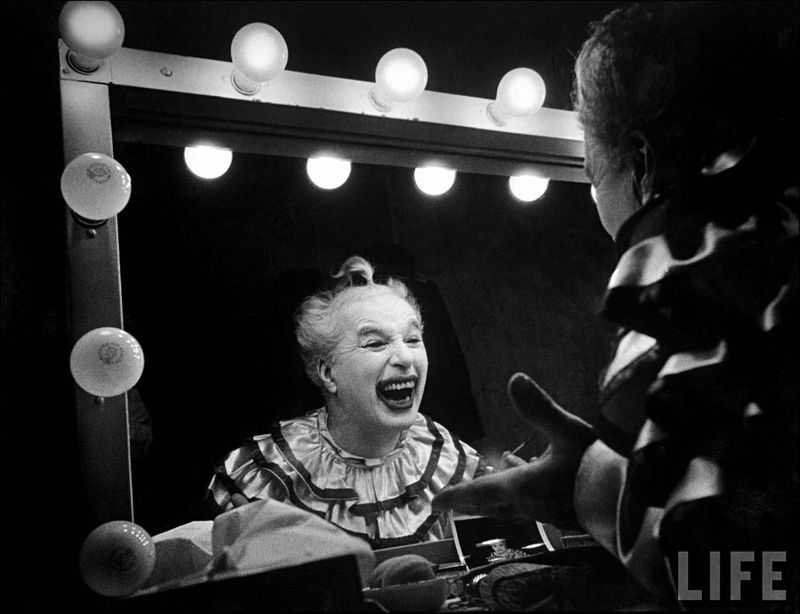

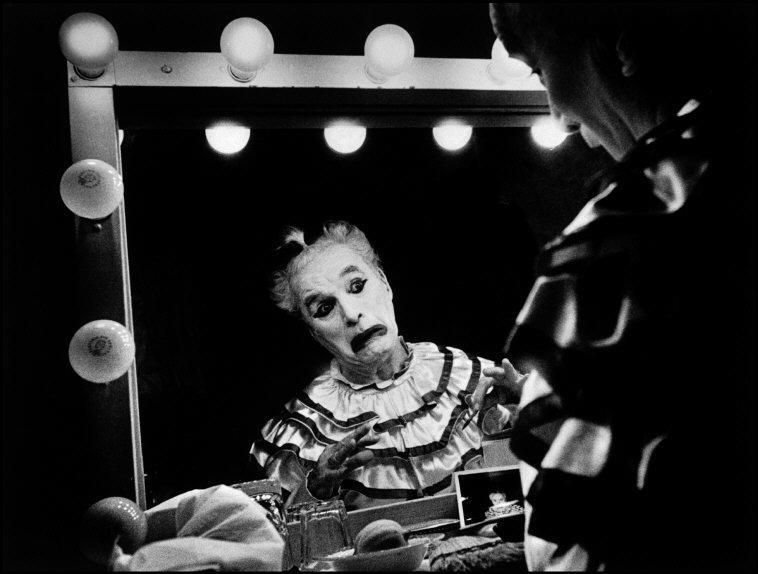

Charlie Chaplin durante el rodaje de su película “Candilejas”. Hollywood, California, 1952.

//

Charlie Chapin during the shooting of his movie “Limelight”. Hollywood, California, 1952,

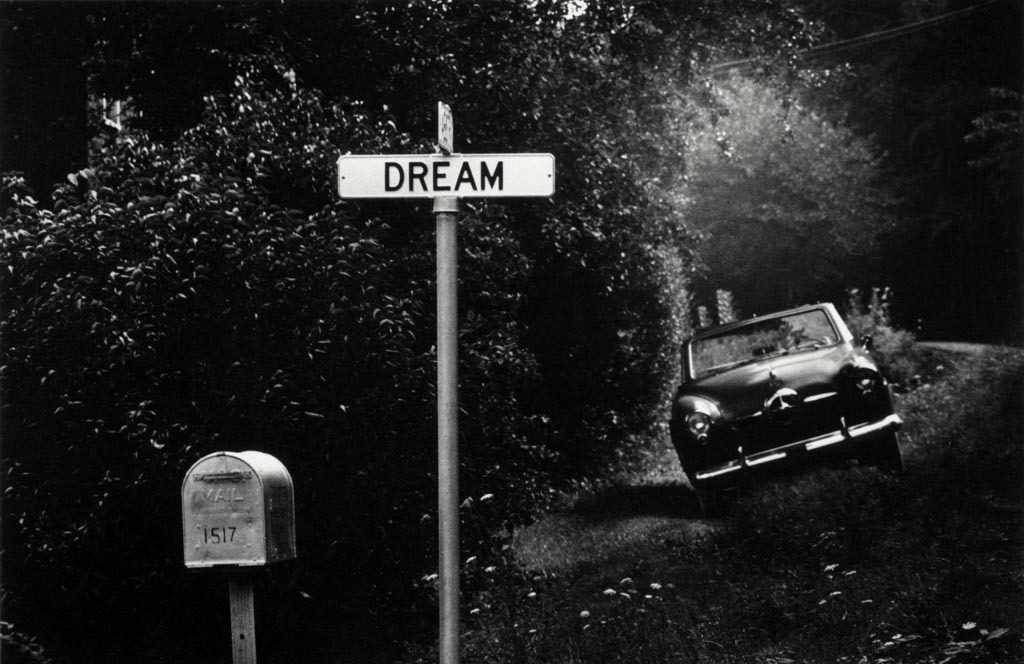

“En la música todavía prefiero las tonalidades menores, y en la impresión me gusta la luz que viene de la oscuridad. Me gustan las imágenes que vencen a la oscuridad, y muchas de mis fotografías son de esa manera. Es mi forma de ver fotográficamente. Por razones prácticas, creo que se ve mejor en la impresión también.” – W. Eugene Smith

//

“In music I still prefer the minor key, and in printing I like the light coming from the dark. I like pictures that surmount the darkness, and many of my photographs are that way. It is the way I see photographically. For practical reasons, I think it looks better in print too.” – W. Eugene Smith

“Nunca he encontrado los límites del potencial fotográfico. Cada horizonte al ser alcanzado, revela otro atrayente en la distancia. Siempre estoy en el umbral.” – W. Eugene Smith

//

“I’ve never found the limits of the photographic potential. Each horizon to be reached, reveals another one appealing in the distance. I’m always on the threshold.” – W. Eugene Smith

Minamata, al sur de Japón. En los años cincuenta, los habitantes detectan un mal extraño que afecta a los animales y después a los humanos y provoca lesiones neurológicas y malformaciones físicas. El mercurio arrojado al mar por la empresa química Chisso contamina toda la cadena alimenticia. Serán necesarios veinticinco años de lucha encarnizada para que los culpables sean condenados. Aún hoy se llevan a cabo diligencias relacionadas con el pago de las indemnizaciones. Oficialmente, son 14.000 las víctimas del mal de Minamata, de las cuales 1.000 han muerto.

“Se llama Tomoko Uemura. El mercurio en el vientre de su madre la envenenó”. Éste es el pie con el que se publicó esta foto del baño de Tomoko, cuya contemplación es poco menos que insoportable, en junio de 1972, en la revista Life: “Hablo por los que no tienen voz”, decía W. Eugene Smith, que dio a conocer la contaminación de Minamata en 1970. “Decidimos apoyar la resistencia de los habitantes”, explica su viuda Aileen. “Para nosotros era un deber moral”. La pareja se instala en una casa de adobe, muy cerca de la familia de Tamoko: “Todos los días veíamos pasar a la madre con ella a la espalda. Eugene se dio cuenta de que esa imagen encerraba un mensaje poderosísimo”. El fotógrafo propone una sesión de fotos y sugiere el momento del baño. La madre de Tomoko acepta, “para mostrar al mundo lo que la contaminación le había hecho a su hija”. Se dan cita una tarde, a la hora tradicional de las abluciones. Un hilo de luz entra suavemente por una ventana lateral. El fotógrafo añade dos lámparas de flash para acentuar el juego de sombras. Lentamente, la madre entra en la bañera con su hija inerte en brazos. “Con los ojos llenos de lágrimas. Eugene hace cinco o seis fotos. Sabía lo que quería”. Por fin, una foto cuya intensidad quema la película con sus miembros atrofiados fuera del agua y el rostro que busca la mirada amorosa de la madre. Tomoko parece sonreír. “Es una imagen de amor”, dijo el fotógrafo.

//

Minamata, south of Japan. In the fifties, people sense a strange evil that affects animals and then to humans and causes serious neurological and physical malformations. The mercury dumped into the sea by the Chisso chemical company contaminated the food chain. It will take twenty five years of bitter struggle for the guilty to be convicted. Even today perform procedures related to the payment of compensation. Officially, 14,000 are victims of Minamata disease, of which 1,000 have died.

“Tomoko Uemura is called. Mercury in the womb of his mother poisoned her”. This is the foot with which this photo of Tomoko bath was published, whose contemplation is nothing short of overwhelming, in June 1972, in Life magazine: “I speak for the voiceless”, said W. Eugene Smith, who released Minamata pollution in 1970. “We decided to support the resistance of the inhabitants”, says his widow Aileen. “For us it was a moral duty”. The couple moved to an adobe house, close Tamoko Family: “Everyday we saw the mother go with her to the back. Eugene realized that image contained a powerful message”. Photographer proposes a photoshoot and suggests bath time. Tomoko’s mother agrees “to show the world what pollution had done to his daughter”. It brings together one afternoon, when traditional ablutions. A thread of light gently enters through a side window. Photographer adds two flash lamps to accentuate the play of shadows. Slowly, the mother goes into the tub with her inert daughter in her arms. “With eyes full of tears. Eugene takes five or six pictures. Knew what he wanted”. Finally, a picture whose intensity burn movie with atrophied limbs out of the water and face seeking mother’s loving gaze. Tomoko semms to smile. “It’s a picture of love”, said the photographer.

“Nunca he econtrado los límites al potencial fotográfico. Cada horizonte, una vez alcanzado, revela otro objetivo haciendo señales en la distancia. Siempre estoy en el umbral.” – W. Eugene Smith

//

“Never have I found the limits of the photographic potential. Every horizon, upon being reached, reveals another beckoning in the distance. Always, I am on the threshold.” – W. Eugene Smith

El ensayo fotográfico “Médico rural” fue un retrato íntimo de la vida y la muerte en la localidad rural de la pequeña población Kremmling, en Colorado. Ernest Ceriani fue el médico que Smith siguió como la sombra durante 23 días, capturando el drama en los acontecimientos cotidianos en la pequeña ciudad. Smith logra esta intimidad extraordinaria, según sus propias palabras, “desapareciendo en el fondo de pantalla”. W. Eugene Smith fotografió este ensayo fotográfico en 1948 para la revista Life. El artículo comienza así: “El pueblo de Kremmling Colorado, 115 kilómetros al oeste de Denver, contiene 1000 personas. El área circundante de unos 400 kilómetros cuadrados, lleno de ranchos que se extienden a lo alto de las Montañas Rocosas, contiene 1000 más. Estas 2000 almas están constantemente cayendo enfermas, recuperándose o muriendo, teniendo hijos, siendo pateados por los caballos o cortándose a sí mismos con botellas rotas. Un solo médico rural, conocido en la profesión como un “g.p.”, o médico general, se hace cargo de todos ellos. Su nombre es Ernest Guy Ceriani. “El encargo no estuvo exento de problemas, ya que Smith ignoró las imágenes propuestas por revista Life y los plazos estrictos, aunque el ensayo publicado se convirtió en un punto de referencia para ensayos de imagen y de fotoperiodismo en las décadas de los 40 y 50.

//

The Country Doctor photo essay was an intimate portrait of life and death in the a small rural town of Kremmling, Colorado. Ernest Ceriani was the doctor that Smith shadowed for 23 days, capturing the drama in everyday events in the small town. Smith achieved this extra- ordinary intimacy by, in his own words, “Fading into the wallpaper”. W. Eugene Smith photographed this 1948 photographic essay for Life magazine. The article begins: “The town of Kremmling Colorado, 115 miles west of Denver, contains 1,000 people. The surrounding area of some 400 square miles, filled with ranches which extend high into the Rocky Mountains, contains 1,000 more. These 2,000 souls are constantly falling ill, recovering or dying, having children, being kicked by horses and cutting themselves on broken bottles. A single country doctor, known in the profession as a “g.p.”, or general practitioner, takes care of them all. His name is Ernest Guy Ceriani.” The assignment was not without it’s problems, as Smith ignored Life Magazine’s proposed images and strict deadlines, but the published essay became a benchmark for picture essays and photojournalism in the 1940’s and 50’s.

(via: http://www.olicito.de/blog/photographer-spotlight)

Tras las heridas sufridas en la II Guerra Mundial, el fotógrafo W. Eugene Smith estuvo dos años sin poder realizar una sola fotografía. Con la retina aún inundada por las dantescas imágenes bélicas, decidió que la primera que hiciera tras un silencio tan largo, representaría todo lo contrario a cuanto había visto en los campos de batalla. El nihilismo daría paso a la inocencia, la negrura a la luz, la muerte a la vida, el pasado al futuro. Se trataba de dejar atrás la sinrazón y el miedo, y para todo ello eligió a sus dos hijos como modelos. Ignoramos lo que el viaje iniciático que con tanta ligereza como decisión emprenden les deparará. Es un túnel de luz quien les reclama y convoca. Ellos, claro, lo ignoran, pero su padre, el propio fotógrafo, se ha quedado unos cuantos metros detrás para cubrirles las espaldas. Sabe que, después de todo, entre los árboles bien se puede hallar escondido algún ogro francotirador. En ese caso, prefiere ser él quien dispare primero.

Esta fotografía ha sido considerada durante muchos años como la mejor fotografía de la historia.

//

Following injuries sustained in World War II, the photographer W. Eugene Smith spent two years unable to make a single photograph. With the retina still flooded with horrific images of war, he decided that the first to do so after a long silence, would represent the opposite of what had been seen in the battlefields. Nihilism would lead to innocence, from darkness to light, from death to life, from past to the future. It was to leave behind the nonsense and move beyond fear, and for that all he elected to their two children as models. We ignore what the journey of initiation that decision so lightly as they embark bring. It is a tunnel of light who is demanding and calling them. They, of course, ignore it, but their father, the photographer himself, has run a few yards behind to cover themselves. He knows that, after all, the trees may well find some ogre hidden sniper. In that case, he prefers to be he who shoots first.

This photo has been considered for many years as the best picture ever.