En septiembre de 1933, el fotógrafo de la revista LIFE Alfred Eisenstaedt viajó a Ginebra para documentar una reunión de la Liga de las Naciones. Una de las figuras políticas en la reunión fue el ministro de propaganda nazi Joseph Goebbels, uno de los subordinados de Hitler más devotos y un hombre que se hizo conocido por su “antisemitismo homicida”.

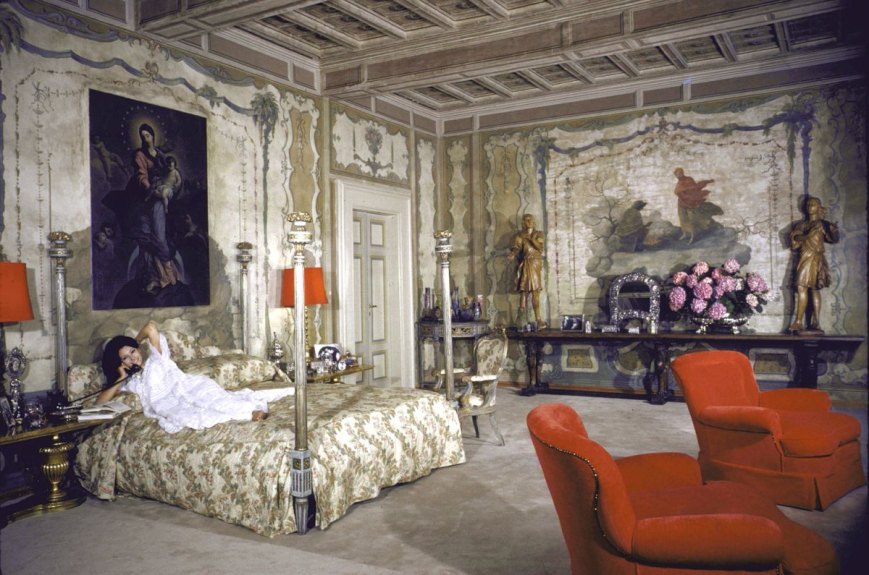

Eisenstaedt era un judío nacido en Alemania. Sin saber esto al principio, Goebbels fue inicialmente amistoso hacia Eisenstaedt, quien fue capaz de capturar una serie de fotos que muestran el político nazi de buen humor y alegre (como en la fotografía de arriba).

Sin embargo, Goebbels pronto se enteró de la sangre que fluía por las venas judías de Eisenstaedt. Posteriormente, cuando Eisenstaedt se acercó a Goebbels para un retrato sincero, la expresión del político fue muy, muy diferente. En lugar de sonreír, frunció el ceño ante la cámara, y la famosa foto resultante muestra el hombre con “ojos de odio”.

Esto es lo que Eisenstaedt compartió más tarde en relación con esta experiencia:

“Lo encontré sentado solo en una mesa plegable en el jardín del hotel. Le fotografié desde la distancia sin que él fuese consciente de ello. Como reportaje documental, la imagen puede tener algún valor: sugiere su alejamiento. Más tarde le encontré en la misma mesa rodeado de ayudantes y guardaespaldas. Goebbels parecía tan pequeño, mientras que sus guardaespaldas eran enormes. Me acerqué y fotografié a Goebbels. Fue horrible. Me miró con una expresión llena de odio. el resultado sin embargo, fue una fotografía mucho más fuerte. No hay sustituto para el contacto personal cercano y la involucración con un sujeto, por muy desagradable que sea.”

y:

“Me miró con los ojos llenos de odio y esperó que me marchitarse. Pero no me marchité. Si tengo una cámara en la mano, no conozco el miedo.”

Esta fotografía de gran alcance se convertiría en una de las imágenes más famosas de Eisenstaedt, aunque él llegó a disparar una aún más emblemática pocos meses después, cuando Goebbels se suicidó al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial.

//

In September 1933, LIFE magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt traveled to Geneva to document a meeting of the League of Nations. One of the political figures at the gathering was Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, one of Hitlers most devout underlings and a man who became known for his “homicidal anti-Semitism.”

Eisenstaedt was a German-born Jew. Not knowing this at first, Goebbels was initially friendly toward Eisenstaedt, who was able to capture a number of photos showing the Nazi politician in a good and cheerful mood (as in the photograph above).

However, Goebbels soon learned of the Jewish blood flowing through Eisenstaedt’s veins. Subsequently, when Eisenstaedt approached Goebbels for a candid portrait, the politician’s expression was very, very different. Instead of smiling, he scowled for the camera, and the famous photo that resulted shows the man wearing “eyes of hate”.

Here’s what Eisenstaedt later shared regarding experience:

“I found him sitting alone at a folding table on the lawn of the hotel. I photographed him from a distance without him being aware of it. As documentary reportage, the picture may have some value: it suggests his aloofness. Later I found him at the same table surrounded by aides and bodyguards. Goebbels seemed so small, while his bodyguards were huge. I walked up close and photographed Goebbels. It was horrible. He looked up at me with an expression full of hate. The result, however, was a much stronger photograph. There is no substitute for close personal contact and involvement with a subject, no matter how unpleasant it may be.”

and:

“He looked at me with hateful eyes and waited for me to wither. But I didn’t wither. If I have a camera in my hand, I don’t know fear.”

This powerful photograph would become one of Eisenstaedt’s most famous images, though he did shoot an even more iconic just months after Goebbels committed suicide at the end of World War II.

(via: http://www.petapixel.com/)

Compartir esto // Share this: