Durante un viaje de trabajo a Madrid, he tenido la oportunidad de ver una fantástica exposición de fotografías de Jacques Henri Lartigue. Era inevitable redactar una entrada en este blog, y tras buscar durante un rato, he encontrado este magnífico artículo de Laura G. Torres, que me permito extractar:

Durante un viaje de trabajo a Madrid, he tenido la oportunidad de ver una fantástica exposición de fotografías de Jacques Henri Lartigue. Era inevitable redactar una entrada en este blog, y tras buscar durante un rato, he encontrado este magnífico artículo de Laura G. Torres, que me permito extractar:

UN MUNDO FLOTANTE. Fotografias de Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986)

Es uno de los grandes nombres de la fotografía del siglo XX y, por primera vez, en España se le dedica una gran exposición antológica. Después de su paso por Barcelona, CaixaForum Madrid acoge la obra del francés Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986), el fotógrafo que quería conservar la felicidad, la fragilidad del instante y “atrapar el propio asombro”, en sus palabras, de un mundo del que eliminó la fealdad de las guerras que le tocó vivir.

“Un mundo flotante. Fotografías de Jacques Henri Lartigue”, reúne más de 200 piezas procedentes de la Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue -la institución estatal que conserva su legado-, entre copias modernas e instantáneas originales reveladas por el propio artista, algunas de las cámaras fotográficas que usó y tomos del diario fotográfico que empezó con ocho años.

Esta exposición permite ser testigo de un periodo especialmente convulso, el de las dos grandes Guerras Mundiales y de la ocupación nazi de Francia y el del vertiginoso cambio tecnológico y del protagonismo de la mujer, pero desde el punto de vista de Lartigue.

Sus fotografías capturan a la sociedad que vivió esos cambios y sus preocupaciones, a la burguesía francesa de principios del XX, pero bajo la apariencia de la felicidad y la ligereza, de la inocencia, la espontaneidad y la alegría de vivir.

Lartigue prácticamente vino al mundo con una cámara fotográfica debajo del brazo. Nacido en Courbevoie, cerca de París, su padre le transmitió su afición a la fotografía regalándole su primera cámara cuando tenía ocho años, en 1902, de madera encerada y con placas de vidrio de 13×18 centímetros, con la que iniciaría un diario fotográfico que le acompañó hasta su muerte a los 92 años.

Pese a su dedicación al arte fotográfico durante más de 80 años -también cultivó la pintura durante un tiempo-, el maestro nunca dejó de considerarse un aficionado, a lo que debió de ayudar su descubrimiento tardío, en 1963 con casi 70 años, por John Szarkowski, conservador de fotografía del MOMA de Nueva York, que le dedicó una exposición. Ese reconocimiento y la gloria que llegó a alcanzar en EE.UU. le convirtieron en profeta en su tierra, donde se convirtió en el retratista oficial del presidente francés Valéry Giscard d’Estaing en 1974.

El francés, que fue un niño enfermizo, se obsesionó con la conservación de la felicidad, con retenerla mediante la escritura, la fotografía y los álbumes, pero siempre bajo la frescura de la juventud, celebrando el instante presente y ocultando la angustia del paso del tiempo.

La muestra se divide en varios apartados que recogen las principales obsesiones del fotógrafo. Una de ellas es el paso del tiempo y la necesidad de convertir la fotografía en instrumento de su memoria y, en conexión, su deseo de fijar la felicidad. Para ello, fotografía el cuerpo humano en movimiento en interacción con el espacio que lo rodea: gente feliz que recibe los embates del oleaje, el viento o los rayos de sol.

Además, Jacques Henri Lartigue fue un innovador del encuadre, que utilizó con gran maestría. Sus instantáneas captadas a ras de suelo, su adaptación a la velocidad de un ciclista, la conversión de lo pequeño en grande o a la inversa, o su manipulación de las imágenes cuando trabaja con la cámara oscura. Luego evolucionó hacia encuadres en los que empleaba los elementos arquitectónicos como una forma de atrapar a los protagonistas.

Otra de sus obsesiones fue captar la realidad física de la velocidad -transportes como el avión revolucionaron la época- y traducir mediante la imagen la emoción que se siente ante la máquina. Así, plasmó las carreras de automóviles y otros deportes de velocidad y fue testigo en 1904 de los intentos de despegue del aviador Gabriel Voisin en Normandía en 1904. Su sueño de volar lo captó en innumerables imágenes de saltos y despegues con las que desafiaba la gravedad.

La exposición también dedica un espacio al particular universo femenino de Lartigue, en el que sólo hay mujeres jóvenes y hermosas, y del que se excluye cualquier deformidad o signo de envejecimiento que pueda recordar a la fealdad o la muerte.

Se convirtió en uno de los primeros fotógrafos de moda cuando se lanzó con 16 años a fotografiar a las mujeres elegantes que paseaban por la avenida del Bois de Boulogne. Su despertar erótico adolescente hizo que las primeras imágenes las captara oculto, con un particular encuadre oblicuo que luego evolucionó a mirar directamente a los ojos de sus amantes que, en contraste con el resto de su obra, aparecen indolentes e inmóviles a petición del autor.

El último espacio de la muestra recoge la fascinación de Lartigue por el infinito y la naturaleza, donde el hombre se enfrenta a la soledad y en la que aparece como un fantasma agitado por los vientos. En una especie de traición a la felicidad que siempre buscó, estas imágenes reflejan que el paso terrenal es efímero.

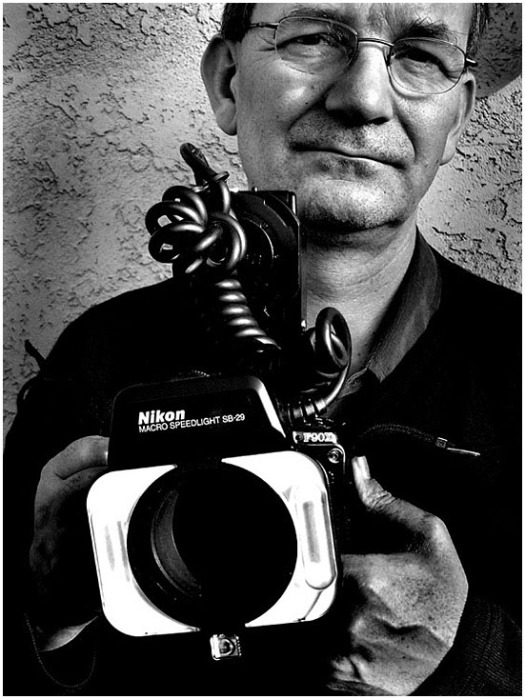

Además de las reproducciones, la exposición muestra muchas de las cámaras usadas por Lartigue, como una Kodak Brownie 2 o una Klapp Nettel de 6×13 centímetros, algunos tirajes realizados por él mismo, álbumes en los que clasifica sus imágenes desde la infancia y retazos de su diario.

La primera cámara del francés fue una estereoscópica Spido Gaumount de placas de vidrio de formato 6×13, que le permitía captar el movimiento. A partir de entonces fue un fiel a la estereoscopia y, aunque sucumbió momentáneamente a la fotografía en color en 1912, como esta no le permitía recoger el movimiento, decidió perpetuar su universo en blanco y negro.

//

During a business trip to Madrid, I’ve had the opportunity to see a fantastic exhibition of photographs by Jacques Henri Lartigue. Inevitably I had to write a post in this blog, and after searching for a while, I found this great article by Laura G. Torres, which I extract here:

A FLOATING WORLD. Photographs by Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986)

One of the great names of twentieth century photography and for the first time in Spain is dedicated a major retrospective. After his stint in Barcelona, Caixa Forum Madrid hosts the work of the Frenchman Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986), the photographer who wanted to keep the happiness, the fragility of the moment and “catch your own astonishment, in his words, a world which eliminated the ugliness of war which he lived.

“A Floating World. Photographs by Jacques Henri Lartigue” gathers over 200 pieces from the Donation Jacques Henri Lartigue, the state agency that preserves his legacy-among modern copies, and original snapshots revealed by the artist, some of the cameras and volumes used photographic photographic diary started eight years.

This exhibition can be seen a particularly turbulent period, the larger of the two World Wars and the Nazi occupation of France and the rapidly changing technological and role of women, but from the point of view of Lartigue.

His photographs capture a society that lived through those changes and their concerns in the French bourgeoisie of early twentieth century, but under the guise of happiness and lightness, innocence, spontaneity and joy of living.

Lartigue practically came to the world with a camera under his arm. Born in Courbevoie, near Paris, his father sent him his love of photography by giving him his first camera when he was eight, in 1902, a polished wood with glass plates 13 x 18 cm, with whom he would launch a photo journal who accompanied him until his death at age 92.

Despite his dedication to the art of photography for over 80 years, he also cultivated the painting for a while, “the teacher never longer considered an amateur, to which must have helped her discovery late in 1963 with nearly 70 years, John Szarkowski, curator of photography at MOMA in New York, an exhibition dedicated to him. This recognition and the glory which reached U.S. made him a prophet in his homeland, where he became the official portrait of French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in 1974.

The Frenchman, who was a sickly child, he became obsessed with the preservation of happiness, to retain it through writing, photography and albums, but always under the freshness of youth, celebrating the present moment and hiding the anguish of the passage of time.

The exhibition is divided into various sections that present the main obsessions of the photographer. One is the passage of time and the need to convert the picture into an instrument of his memory and, in conjunction, their desire to secure happiness. To do this, he captures the human body in motion in interaction with the surrounding space: Happy people who get the brunt of the waves, wind or sunshine.

In addition, Jacques Henri Lartigue was an innovator of the setting, used with great skill. His snapshots taken at ground level, to adapt to the speed of a cyclist, the conversion of large or small in reverse, or manipulation of images when working with the camera obscura. Then it evolved into frames in which the architectural elements used as a way to catch the players.

Another of his obsessions was to capture the physical reality-transport speed as the airplane revolutionized the time-and translate the image by the thrill at the typewriter. Thus, shaped the careers of other sports cars and speed and in 1904 saw attempts Gabriel Voisin flyer off to Normandy in 1904. His dream of flight captured it in countless pictures of jumps and take-offs that defied gravity.

The exhibition also devotes considerable space to particular Lartigue feminine universe, where there is only young, beautiful women and which excludes any deformity or signs of aging that can remember the ugliness or death.

He became one of the first fashion photographers when it was launched 16 years to photograph the elegant women walking along the Avenue Bois de Boulogne. Teenager made his erotic awakening that would capture first images of the occult, with a particular oblique frame then evolved to look directly into the eyes of her lovers, in contrast to the rest of his work appear sluggish and immobile at the request of the author.

The last area of the exhibition includes Lartigue’s fascination with the infinite nature, where man confronts the loneliness and appears as a ghost agitated by the winds. In a kind of betrayal of the happiness that has always sought, these images show that the passage on earth is fleeting.

In addition to the prints, the exhibition shows many of the cameras used by Lartigue, a Kodak Brownie Nettel Klapp 2 or 6 x 13 cm, some runs made by himself, albums in which classified the images from childhood and pieces from his diary.

The French first camera was a Gaumount Spido stereoscopic glass plates 6 x 13 format, which allowed him to capture movement. Thereafter it was a faithful and stereoscopy, though momentarily succumbed to color photography in 1912, as this is not allowed to pick up the movement, decided to perpetuate his black and white universe.

Compartir esto // Share this:

“Helen Levitt. Lyric urban. Photographs 1936-1993” includes 120 images and a video on the city of New York that show how the city that never sleeps actually never sleeps, but it does change.

“Helen Levitt. Lyric urban. Photographs 1936-1993” includes 120 images and a video on the city of New York that show how the city that never sleeps actually never sleeps, but it does change.

Garry Winogrand, artista norteamericano, está considerado como un renovador de la fotografía del siglo XX. Durante los años 1960 y 1970 captó la transformación de la mujer y su evolución en la sociedad. La colección Women are beautiful, está formada por 85 fotografías también recogidas por John Szarkowski, director del departamento de fotografía del MoMA, en un libro que recibe el mismo nombre de la exposición.

Garry Winogrand, artista norteamericano, está considerado como un renovador de la fotografía del siglo XX. Durante los años 1960 y 1970 captó la transformación de la mujer y su evolución en la sociedad. La colección Women are beautiful, está formada por 85 fotografías también recogidas por John Szarkowski, director del departamento de fotografía del MoMA, en un libro que recibe el mismo nombre de la exposición. Garry Winogrand, American artist, is considered an innovator of the twentieth-century photography. During the 1960 and 1970 captured the transformation of women and developments in society. Women are beautiful collection is made up of 85 photographs also collected by John Szarkowski, director of MoMA’s photography department, in a book bearing the same name of the exhibition.

Garry Winogrand, American artist, is considered an innovator of the twentieth-century photography. During the 1960 and 1970 captured the transformation of women and developments in society. Women are beautiful collection is made up of 85 photographs also collected by John Szarkowski, director of MoMA’s photography department, in a book bearing the same name of the exhibition.

Durante 50 años el fotógrafo André Kertész tomó fotografías de gente leyendo. Su libro seminal “On Reading” presenta una serie de estas fotografías tomadas por Kertész en Hungría, Francia y Estados Unidos. Fue publicado por primera vez en 1971 en Nueva York, por la Editorial Grossman y ahora ha sido reeditado por W.W. Norton.

Durante 50 años el fotógrafo André Kertész tomó fotografías de gente leyendo. Su libro seminal “On Reading” presenta una serie de estas fotografías tomadas por Kertész en Hungría, Francia y Estados Unidos. Fue publicado por primera vez en 1971 en Nueva York, por la Editorial Grossman y ahora ha sido reeditado por W.W. Norton.

“Todo el mundo fotografía a los pobres, así que yo decidí que quería fotografiar a los ricos”, señala Martin Parr en una conversación telefónica. “Es algo que inspira poca confianza. Está claro que fotografiar una guerra da más prestigio, no hay discusión, pero seguir el rastro de la clase media o, ahora, de los nuevos ricos no despierta demasiado interés”.

“Todo el mundo fotografía a los pobres, así que yo decidí que quería fotografiar a los ricos”, señala Martin Parr en una conversación telefónica. “Es algo que inspira poca confianza. Está claro que fotografiar una guerra da más prestigio, no hay discusión, pero seguir el rastro de la clase media o, ahora, de los nuevos ricos no despierta demasiado interés”. “Everybody photograph to the poor, so I decided I wanted to photograph the rich,” says Martin Parr in a telephone conversation. “It’s something that inspires little confidence. It is clear that a war photograph gives more prestige, no discussion, but keep track of the middle class or, now, the new rich do not wake up too interested.”

“Everybody photograph to the poor, so I decided I wanted to photograph the rich,” says Martin Parr in a telephone conversation. “It’s something that inspires little confidence. It is clear that a war photograph gives more prestige, no discussion, but keep track of the middle class or, now, the new rich do not wake up too interested.”

Eugène Atget no se formó como fotógrafo: llegó a la fotografía buscando un mejor sustento tras haber probado suerte en otros medios. Comenzó su carrera en provincias, pero pronto llegó a París, donde permaneció hasta el final de su vida. Atget trabajó en el anonimato. Era considerado un fotógrafo comercial que vendía lo que él denominaba “documentos para artistas”: paisajes, primeros planos, escenas de género, detalles que servían como modelo a pintores. No obstante, en el momento en el que se centra en las calles de París, llamó la atención de prestigiosas instituciones, tales como el Musée Carnavalet y la Bibliothéque Nationale, que se convirtieron en sus principales clientes.

Eugène Atget no se formó como fotógrafo: llegó a la fotografía buscando un mejor sustento tras haber probado suerte en otros medios. Comenzó su carrera en provincias, pero pronto llegó a París, donde permaneció hasta el final de su vida. Atget trabajó en el anonimato. Era considerado un fotógrafo comercial que vendía lo que él denominaba “documentos para artistas”: paisajes, primeros planos, escenas de género, detalles que servían como modelo a pintores. No obstante, en el momento en el que se centra en las calles de París, llamó la atención de prestigiosas instituciones, tales como el Musée Carnavalet y la Bibliothéque Nationale, que se convirtieron en sus principales clientes.

(por Antoni Pedragosa, en

(por Antoni Pedragosa, en  (by Antoni Pedragosa, in

(by Antoni Pedragosa, in

“Color del Sur” recopila una selección de 40 fotografías de gran tamaño, que forman parte de las 70 imágenes de la exposición de Pérez Siquier y que recientemente han sido adquiridas por la entidad financiera Unicaja. Las imágenes fueron tomadas por el artista entre 1970 y 1980 en las localidades almerienses de Roquetas de Mar, Aguadulce, Playa Serena, Almerimar, Cabo de Gata, San José, La Isleta del Moro, las Negras y Rodalquilar y en las localidades malagueñas de Torremolinos y Marbella; así como entre 1990 y 2000 en la provincia de Almería.

“Color del Sur” recopila una selección de 40 fotografías de gran tamaño, que forman parte de las 70 imágenes de la exposición de Pérez Siquier y que recientemente han sido adquiridas por la entidad financiera Unicaja. Las imágenes fueron tomadas por el artista entre 1970 y 1980 en las localidades almerienses de Roquetas de Mar, Aguadulce, Playa Serena, Almerimar, Cabo de Gata, San José, La Isleta del Moro, las Negras y Rodalquilar y en las localidades malagueñas de Torremolinos y Marbella; así como entre 1990 y 2000 en la provincia de Almería.

Durante un viaje de trabajo a Madrid, he tenido la oportunidad de ver una fantástica exposición de fotografías de Jacques Henri Lartigue. Era inevitable redactar una entrada en este blog, y tras buscar durante un rato, he encontrado este magnífico artículo de Laura G. Torres, que me permito extractar:

Durante un viaje de trabajo a Madrid, he tenido la oportunidad de ver una fantástica exposición de fotografías de Jacques Henri Lartigue. Era inevitable redactar una entrada en este blog, y tras buscar durante un rato, he encontrado este magnífico artículo de Laura G. Torres, que me permito extractar:

Escribe Sebastiao Salgado: «El cualquier situación de crisis, ya se trate de guerras, pobreza o catástrofes naturales, los niños son las mayores víctimas. Son los más débiles físicamente, y siempre son los primeros en sucumbir a las enfermedades o al hambre. Muy vulnerables emocionalmente, los niños son incapaces de entender por qué les obligan a abandonar sus casas, por qué sus vecinos se convierten en enemigos, por qué de repente tienen que vivir en un arrabal rodeados de basura o en un campo de refugiados sumido en la desgracia. No son responsables de su destino, ya que, por definición, son inocentes».

Escribe Sebastiao Salgado: «El cualquier situación de crisis, ya se trate de guerras, pobreza o catástrofes naturales, los niños son las mayores víctimas. Son los más débiles físicamente, y siempre son los primeros en sucumbir a las enfermedades o al hambre. Muy vulnerables emocionalmente, los niños son incapaces de entender por qué les obligan a abandonar sus casas, por qué sus vecinos se convierten en enemigos, por qué de repente tienen que vivir en un arrabal rodeados de basura o en un campo de refugiados sumido en la desgracia. No son responsables de su destino, ya que, por definición, son inocentes».  Sebastiao Salgado writes: “On any crisis, be it war, poverty or natural disasters, children are the biggest victims. They are physically weaker, and they are always the first to succumb to disease or starvation. Emotionally vulnerable, children are unable to understand why they are forced to flee their homes, why your neighbors become enemies, why suddenly they have to live in a suburb surrounded by trash or in a refugee camp deep in the Unfortunately. They are not responsible for their fate, since, by definition, they are innocent. ”

Sebastiao Salgado writes: “On any crisis, be it war, poverty or natural disasters, children are the biggest victims. They are physically weaker, and they are always the first to succumb to disease or starvation. Emotionally vulnerable, children are unable to understand why they are forced to flee their homes, why your neighbors become enemies, why suddenly they have to live in a suburb surrounded by trash or in a refugee camp deep in the Unfortunately. They are not responsible for their fate, since, by definition, they are innocent. ”