“Creo que la fotografía ama los objetos banales, y yo amo la vida de los objetos.” – Josef Sudek

//

“I believe that photography loves banal objects, and I love the life of objects.” – Josef Sudek

“Creo que la fotografía ama los objetos banales, y yo amo la vida de los objetos.” – Josef Sudek

//

“I believe that photography loves banal objects, and I love the life of objects.” – Josef Sudek

Jaroslav Seifert, poeta checo del siglo XX, describe la personalidad de Josef Sudek en uno de los capítulos de su libro en prosa “Toda la belleza del mundo”:

“Clavó el trípode en el musgo, se había fijado en una raíz rojiza y retorcida junto a la que yo había pasado sin advertirla. Se instaló encima de ella, dio unos pasos atrás y volvió al aparato. Las raíces oprimían una piedra resquebrajada como abrazándola. Cuando, más tarde, vi en casa de Sudek aquella fotografía, no daba crédito a mis ojos. ¡La raíz era en la foto tan hermosa como una escultura de Miguel Angel!. Y luego dicen que la fotografía no es arte.”

//

Jaroslav Seifert, Czech poet of the twentieth century, describes the personality of Josef Sudek in one of the chapters of his book in prose “The whole beauty of the world”:

“He dug the tripod in the moss, had noticed a red and gnarled root beside which I had passed without warning. He settled over it, stepped back and returned to the device. The roots were oppressing a stone cracked like hugging it. When, later, I saw that photograph at Sudek house, I could not believe my eyes. The root was so beautiful picture as a sculpture of Miguel Angel!. And they say that photography is not art.”

(via: https://umelecky.wordpress.com/2016/02/28/josef-sudek%e2%80%8f-un-poeta-de-la-imagen/)

“Me encanta la vida de los objetos. Cuando los niños se van a la cama, los objetos cobran vida. Me gusta contar historias sobre la vida de objetos inanimados.” – Josef Sudek

//

“I love the life of objects. When the children go to bed, the objects come to life. I like to tell stories about the life of inanimate objects.” – Josef Sudek

“Creo mucho en el instinto. Uno nunca debería aburrirse queriendo saberlo todo. No hay que hacer demasiadas preguntas, sino hacer lo que uno hace correctamente, nunca con prisa, y nunca atormentándose a uno mismo.” – Josef Sudek

//

“I believe a lot in instinct. One should never dull it by wanting to know everything. One shouldn’t ask too many questions but do what one does properly, never rush, and never torment oneself.” – Josef Sudek

“Todo cuanto nos rodea, vivo o muerto, adopta misteriosamente multitud de variaciones a ojos de un fotógrafo loco, de manera que un objeto en apariencia muerto cobra vida a través de la luz o gracias a su entorno.” – Josef Sudek

//

“Everything around us, dead or alive, mysteriously takes many variations eyes of a crazy photographer, so that an object that looks dead come to life through light or by its surroundings.” – Josef Sudek

“…todo lo que nos rodea, vivo o muerto, a los ojos de un fotógrafo loco lleva misteriosamente a muchas variaciones, por lo que un objeto aparentemente muerto vuelve a la vida a través de la luz o por lo que le rodea… para captar parte de este – Supongo que eso es sentimentalismo.” – Josef Sudek

//

“…everything around us, dead or alive, in the eyes of a crazy photographer mysteriously takes on many variations, so that a seemingly dead object comes to life through light or by its surroundings… to capture some of this – I suppose that’s lyricism.” – Josef Sudek

No encuentro otra forma mejor de felicitar la Navidad que con estas fantásticas fotografías llenas de nostalgia de Josef Sudek.

Feliz Navidad a todos!

//

I can not find a better way to congratulate Christmas with these great pictures full of nostalgia by Josef Sudek.

Merry Christmas to everyone!

En la historia de la fotografía mundial, las posiciones importantes fueron ocupadas en primer lugar por personalidades cuyo trabajo estuvo marcado por una característica y, por otra parte, por la excepcional artesanía en su propio tiempo. Josef Sudek, quien entre todos los fotógrafos de Checoslovaquia se convirtió, sin duda, en el más conocido incluso más allá de los límites de su propia tierra, cumplió directamente estas condiciones de una forma ejemplar. El carácter individual de sus imágenes estaba estrechamente relacionado con su fidelidad absoluta a sus propios principios y con una aversión a adaptarse a los modelos extranjeros, incluso si éstos tenían el más amplio reconocimiento. Sudek estaba libre del deseo por un gran éxito y quizás por esta razón pudo disfrutar de ello al máximo. Más tarde, en el momento en que ya era famoso, admitió que nunca había contado con un mayor impacto de sus imágenes a las cuales les dió rigurosa forma en el modo que, como él sentía, requería su arte creativo.

//

In the history of the world photography significant positions were held first of all by personalities whose work was marked by a characteristic and, moreover, exceptional craftsmanship in its own time. Josef Sudek, who among all Czechoslovak photographers became doubtlessly the best known even beyond the boundaries of his own land, fulfilled these conditions directly in an exemplary manner. The individual character of his pictures was closely connected with his utter faithfulness to his own principles and with an aversion to adapt himself to any foreign models, even if these met with wider acknowledgement. Sudek was free from the desire for great success and perhaps for this reason he could enjoy it to the full. Later on, at the time when he was already famous, he admitted that he had never counted with a wider impact of his pictures which he shaped rigorously in the way which, as he felt, his creative art required.

(via: http://5election.com/)

(Por Jesús Marchamalo:)

Debía resultar una figura imponente, algo irreal, fantasmagórica, en aquella Praga brumosa, nocturna, de parques y avenidas solitarias que con tanta intensidad supo captar en sus fotografías. Pelo ralo, a menudo despeinado, barba descuidada, ojos risueños, vivarachos, solía vestir un amplio abrigo, oscuro, a veces un capote militar, y una enorme cámara cargada sobre el hombro. Una antigua Kodak de caja de madera, cuyo trípode utilizaba como contrapeso, sosteniéndolo con su único brazo.

Debía resultar una figura imponente, algo irreal, fantasmagórica, en aquella Praga brumosa, nocturna, de parques y avenidas solitarias que con tanta intensidad supo captar en sus fotografías. Pelo ralo, a menudo despeinado, barba descuidada, ojos risueños, vivarachos, solía vestir un amplio abrigo, oscuro, a veces un capote militar, y una enorme cámara cargada sobre el hombro. Una antigua Kodak de caja de madera, cuyo trípode utilizaba como contrapeso, sosteniéndolo con su único brazo.

A pesar de su aspecto inconfundible, llamativo, debió gozar de ese don que permite a los fotógrafos hacerse invisibles. No aparecen muchas personas en sus fotografías, pero cuando lo hacen, nunca nadie le mira, nadie parece reparar en él; como si no hubiera estado.

Tímido e introvertido –ni siquiera asistía a la inauguración de sus exposiciones-, minucioso y obsesivo en su trabajo, sus instantáneas, muchas de ellas positivadas como contactos, muestran una ciudad neblinosa, oscura y onírica; el poeta de Praga le llamaban.

Nacido en Kolín, Bohemia central, en 1896, huérfano de padre a muy corta edad, Joseph Sudek trabajó como encuadernador hasta que en julio de 1916, en plena Gran Guerra, fue movilizado y enviado al frente italiano, donde resultó herido. La explosión de una granada, disparada al parecer por su propio ejército, le provocó graves daños en el brazo derecho, que acabó perdiendo. De vuelta en Praga, tuvo que abandonar el taller de encuadernación, y la fotografía, que hasta ese momento había sido un mero pasatiempo, se convirtió en su nuevo trabajo.

En los primeros años veinte inició una serie de retratos en la Invaliodvna, el centro de veteranos e inválidos de guerra, al tiempo que abordaba su particular visión de la ciudad: gente caminando o esperando en una parada, estaciones oscuras, intensos contraluces, tranvías solitarios en el Puente de Carlos…

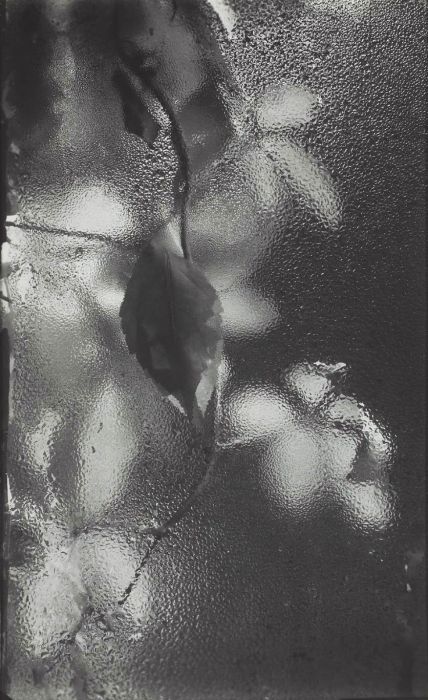

En 1927 Sudek abrió su estudio en una especie de cobertizo de madera en un jardín en Malá Strada, el centro de la ciudad. Allí trabajó hasta su muerte, en 1976, y allí, durante la ocupación nazi, cuando las restricciones impuestas por el ejército alemán limitaban las posibilidades de salir a la calle, empezó a hacer fotografías en su estudio, que convirtió en un auténtico gabinete de curiosidades: su jardín, siempre descuidado, la rama de manzano, una nevada, el otoño… Registraba el cambio de las estaciones, la meteorología, a veces con largas exposiciones de minutos, y fotografiaba las fachadas de los edificios colindantes a través del pequeño cristal de la ventana, empañado y cubierto de vaho.

El caminante se convirtió en un paseante interior, un observador de lo próximo. Comienza entonces a fotografiar muchas de las pequeñas cosas que tiene alrededor, haciendo composiciones que repite de forma obsesiva, desde distintos ángulos y con diferentes iluminaciones. Un mundo de objetos –vasos, floreros, platos de loza-, suyos o que pedía a sus amigos, a través de los cuales trataba de recordarlos, o explicarlos. “Son objetos cotidianos, un poco al estilo de Morandi: esponjas, botellas, una pluma de ave”, es de nuevo Bonet. “Es curioso porque hay elementos muy parecidos en sus mundos. Morandi vivía con sus dos hermanas, al igual que Sudek, cuya hermana era además su ayudante. Son entornos muy pequeños. De Sudek no se conocen fotos de acontecimientos oficiales o políticos. No se sabe mucho, casi nada, de su vida privada. No hay noticia de qué hizo más allá de lo que ha quedado de su obra: un personaje muy concentrado en vivir, pasear, y en mostrar su ciudad, como un topógrafo, casi, un notario, un poeta romántico”.

Durante años fue un paseante solitario, tolerado, extravagante. A su muerte, su estudio, descuidado y abandonado, se quemó en un incendio. Se perdió gran cantidad de papeles y documentos, nunca se supo cuántos. El fotógrafo de Praga, el de los muros, las farolas solitarias y las flores marchitas. La última rosa, se lee en una de las fotos de la exposición: un florero, una concha, dos chinchetas sobre el alfeizar de una ventana.

//

(By Jesús Marchamalo:)

Should be an imposing figure, something unreal, phantasmagoric, on that foggy Prague, by night, the lonely parks and avenues so intensely captured in his photographs. Thinning hair often disheveled, unkempt beard, smiling and vivacious eyes, he used to wear a large overcoat, dark, sometimes a military overcoat, and a huge camera charged on the shoulder. An old wooden box Kodak, which used as a counterweight tripod, holding it with his one arm.

Should be an imposing figure, something unreal, phantasmagoric, on that foggy Prague, by night, the lonely parks and avenues so intensely captured in his photographs. Thinning hair often disheveled, unkempt beard, smiling and vivacious eyes, he used to wear a large overcoat, dark, sometimes a military overcoat, and a huge camera charged on the shoulder. An old wooden box Kodak, which used as a counterweight tripod, holding it with his one arm.

Despite its distinctive appearance, flashy, he should enjoy the gift that allows photographers to become invisible. Not many people appear in his photographs, but when they do, nobody ever looks at him, nobody seems to notice him, as if it had not been.

Shy and introverted -not even attending the opening of his exhibitions-, meticulous and obsessive in his work, their snapshots, many developed as contacts, show a foggy city, dark and dreamlike, the poet of Prague called him.

Born in Kolín, central Bohemia, in 1896, lost his father at an early age, Joseph Sudek worked as a bookbinder until July 1916, in the midst of World War I, was mobilized and sent to the Italian front, where he was wounded. The explosion of a grenade, apparently fired by his own army, severely damaged his right arm, which ended up losing. Back in Prague, he had to leave the bindery, and photography, which until then had been a mere hobby, became his new job.

In the early twenties he began a series of portraits in Invaliodvna, the center of veterans and war invalids, while addressing their particular vision of the city, people walking or waiting at a bus stop stations, dark stations, intense backlighting, solitary trams on the Charles Bridge…

In 1927 Sudek opened his studio in a sort of wooden shed in a garden in Malá Strada, the center of the city. He worked there until his death in 1976, and there, during the Nazi occupation, when the restrictions imposed by the German army limited the possibilities of going outside, he began making photographs in his studio, which became a veritable cabinet of curiosities: his garden, always neglected, an appletree branch, a snowy, autumn… He registered the change of seasons, weather, sometimes with long exposures of minutes, and photographed the facades of nearby buildings through the small glass the window, covered with fog.

The walker became an interior passer, an observer of what’s next. Then begins to photograph many of the small things around, making compositions that repeats obsessively, from different angles and with different lighting. A world of objects -cups, vases, china plates-, from his own or asking them to his friends, through which was to remember them, or explain. “These are everyday objects, some Morandi style: sponges, bottles, a feather,” is again Bonet. “It’s funny because there are very similar elements in their worlds. Morandi lived with his two sisters, as Sudek, whose sister was also his assistant. They are very small environments. Of Sudek not known photos of events or political official. Not much is known almost nothing about his private life. There is no record of what he did beyond what is left of his work: a very concentrated person on living, walking, and to show his city as a surveyor, almost a notary, a romantic poet. ”

For years he was a solitary wanderer, tolerated, extravagant. At his death, his studio, neglected and abandoned, burned in a fire. A lot of papers and documents were missed, never knew how many. The photographer in Prague, with interest on walls, streetlights solitary and withered flowers. The Last Rose, reads one of the photos of the exhibition: a vase, a shell, two pins on the sill of a window.